CAIRO PRACTICE

This month Paul Vernon's time-machine pauses for a look at the early days of

Arab music recording

As the 19th Century gave way to the 20th, Cairo was a cosmopolitan city of more

than a third of a million people, Over 80 per cent were Egyptians, but the balance

was made up of Greeks, Italians, French, Austrians, English, Germans and Turks. The

reason most of them were there was trade. Cairo was, strategically and economically,

the hub of all commerce between Western Europe and the Arab countries.

With a booming economy, a measure of political stability and no immediate threat

of war, successful Egyptians looked for novel ways of using their disposable income.

The great novelty of that era, the talking machine, was therefore in a prime position

to take a handsome slice of new business.

As early as 1894, talking machines and records, available by mail from London

and Paris, had been advertised in the Cairo press. However, the records offered were

those standard mix of Opera, military bands, cornet solos and popular European song.

It became clear to the early record companies that much greater success could be

gained by making records of what they themselves referred to as 'Native Music'. In

the spring of 1903 the London-based Gramophone Company sent engineer Franz Hampe

to Cairo where he made 165 single sided recordings. Later that same year, his endeavours

having been manufactured in London and shipped back to Cairo, the first catalogue

of Arab music was presented to an eager public.

To understand the impact that this innovation had upon its intended audience,

it is necessary to remember that none of them had ever heard a mechanical reproduction

of Culturally relevant music before. As in India, where similar events were occurring

at the same time, the Egyrptians took to the gramophone with an enthusiasm that caused

smiles of satisfaction to cross the faces of record company executives in England.

The following year, competition kicked in with a vengence, German Odeon, newly

formed and very aggressive, sent their recording expert John Daniel Smooth to Cairo

to create a catalogue with which to compete in this fast-expanding market. Within

months, the Gramophone Company's American expatriate expert W. Sinkler Darby had

been despatched to make a series of 12" 78 rpm records to add lustre to their

catalogue. By 1905 the Egyptian music afficionados had been confronted with a considerable

choise.

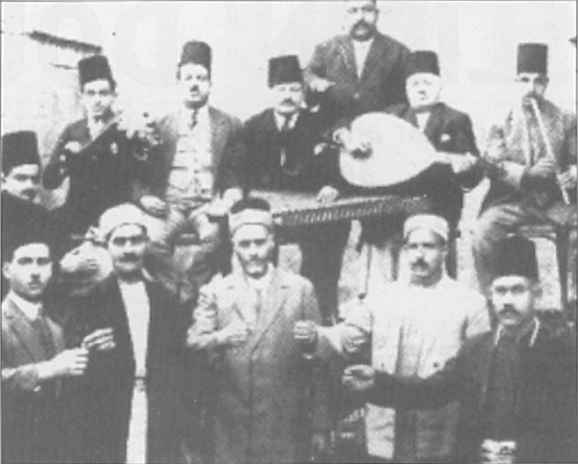

What they were being offered was a remarkable selection of genuine traditional

music. Classical, improvisational, poetic, theatrical and popular styles were all

represented, and the musicians were almost always people who brought a deep understanding

of the idiom to their art.

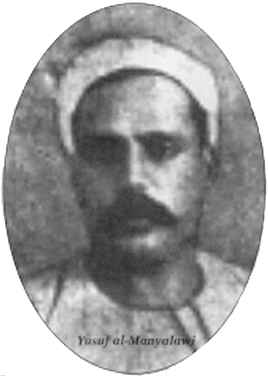

Yusuf al-Manyalawi, the most important of the early singers, had been a court

musician to King Abd al-Hamid and when first recorded by the Gramophone Company,

in about 1905, he was already 65 years old. Held in awe by other musicians and the

public alike, his records were not only commercially successful but also immensely

important artistically. From 1908 until his death in 1911 he recorded extensively

for the Egyptian owned Sama al-Muluk (Choice of Kings) label, an enterprise founded

by local business people specifically to promote his music. Years after his death,

much of his extensive repertoire was still available.

As the public demand for authentic music grew, two things happened. First, more record

companies entered the field. By 1910 French Pathé and the Baidaphon company,

owned and operated not by Europeans but by the Baida brothers, Lebanese businessmen,

had both produced significant bodies of music.

Second the nature of the gramophone itself began to alter the character of the music.

Because it was only possible to record a maximum of three and a half minutes on one

side of a 78 rpm record, many early Egyptian records are at least two parts, and

sometime four spread over two discs. However, the musicians had to stop every time

a side finished and then start again. Not used to these restrictions, some found

difficulty in adjusting to the technology and remained little recorded. Others, Manyalawi

included, adapted well and prospered as a result. The music itself bent to the restrictions

of the fledgling industry.Shorter, through-composed pieces were produced specifically

for recording purposes, and larger instrumental ensembles, difficult to record accurately

in the early acoustic days, were pared down to quartets and trios.

Arguably, then it can be said that the gramophone itself altered the course and character

of Egyptian music. What we hear today in old records has much to do with the technical

limitations of early recording as it does the music itself. That said, what is left

constitutes a remarkable legacy.

Cairo became the centre of all Arab recording activity throughout the first 30

years of this century. From Syria and the Lebanon, from Damascus and Jaffa, artists

travelled to Cairo to record for the major European companies. Seeing this situation

clearly, the Lebanese Baidaphon company set up a Cairene branch office in 1914 and

began making a wide variety of Arabic music available. Algerian, Moroccan and Tunisian

styles are all represented in the early Baidaphon catalogues, along with their competitive

efforts at challenging the major owned company's domestic output.

The 1914-18 war affected business to the degree that, as a result of its outcome,

and Egypt being placed under a British protectorate, only the English Gramophone

Company and French Pathé relocated and started taking recordings elsewhere

in the Middle-East. Pathé concentrated on Algiers, Morocco and Tunisia, perhaps

largely due to their all being French colonies at the time. Odeon also turned its

attention to these areas and both Columbia and Polyphon began building catalogues.

The recording of Arab music was about to enter a new era.

Om Kalsoum

With the perfection of an electrical recording process in 1925, a 30 year period

of exclusivity was drawing to a close. While the gramophone business had been acoustic

in nature, the private ownership of a machine had largely been the privilege of those

with money. This effectively meant that in any country with a class system of any

kind, the proletariat were often excluded and therefore not catered to by the companies.

With the new technology, however, mass production of records became easier and cheaper,

and portable machines had been perfected that could be manufactured and sold cheaply

in large quantities. The result was a world-wide explosion of recording activity

with the mass market as its target. In almost every country, from North America to

Portugal, from Greece to Argentina, a massive explosion of recording activity occurred

from 1926 onwards, one that would last for almost five years!

FoLK ROOTS 27

Throughout the Arab world, the new access to cheap music was met with deep enthusiasm.

Those who could not or did not purchase their own machine were exposed to the medium

in coffee houses. In even the most afflicted low-income areas one could listen to

the gramophone simply by taking a coffee or a nargile. The music spread through rural

Egypt by rudimentary dissemination. In small towns and villages the mayor or elder

often possessed a machine and, in tight-knit communities, publicly shared recitals

were common. Travelling 'Music Men' - street level entrepreneurs with a handcart

mounted wind-up gramophone and a selection of records - earned a living of sorts

by offering to play any tune of choice for a small fee.

Interestingly, this practise was common in India also.

It was in this way that Om Kalsoum first heard recorded music. Her father, a Qur'an

reader in a rural community, had taught her his skills when she was still a child;

growing up with the influence of religious instruction and exposure to both live

and recorded music, her natural skill was recognised early enough to send her to

Cairo for further voice training. By 1926, when Kalsoum was about 22 years old, she

was considered good enough by the Gramophone Company to make commercial records.

Kalsoum's success was almost instant. From her first session, only a year after

recording had gone electric, until her death in 1975, she was Egypt's best loved

and most revered singer. Her records sold in huge quantities and the Gramophone Company

paid her what was then an enormous sum of money - £25 per song - to keep her

services. An interesting insight into Kalsoum, in the form of a letter sent to the

Gramophone Company by the engineer who recorded her, survives;

"Hotel Continental, Cairo, 21/4/29

We are experiencing great difficulty in making arrangements with Omm Koulsoun

(sic), she came to the studios on Friday last at 9.30 after making an appointment

for 7 o'clock. At 10.30 she started singing. After making one title which took an

hour to rehearse she decided it was no good. This is the usual procedure and we are

accustomed to it. Having decided she would sing no more that night she left saying

she would not come again until the 4th of May. This evening she has telephoned saying

she will start recording again on the 29th. You will understand it is impossible

to give any date as to when we are likely to finish.

Faithfully, E. Fowler"

Despite Fowler's complaints, Kalsoum's output remained prodigious.

By 1929 more than725,000 individual recordings of Arab music had been made, an

average of over 275 double sided records a week since recording had begun a quartercentury

earlier. This may take the modern reader somewhat aback. However, several factors

contributed to this staggering figure and they need to be enumerated so that the

statistic can be more fully understood. The 'Arab World', as the early record companies

perceived it, stretched from Morocco to Persia and south into lower Egypt and the,

Sudan, an area larger than the United States. From the record company's point of

view it also y included the United States where, by 1924, there were over 400,000

immigrants of

Arab origin. With no competition from any media other than the silent cinema,

record companies absorbed almost all the disposable income that people spent on passive

entertainment. For the companies, records were easy and cheap to produce. Royalties

were almost unheard of and artists' fees were often at a level that would today be

considered derisory. It was, in short, a fat time for the record industry.

By 1929, statistically the peak year of recording activity world wide, seven separate

companies, five of them European, were actively engaged in recording and selling

almost all forms of Arab music. Significant catalogues of Algerian, Egyptian, Iraqi,

Lebanese, Moroccan, Persian, Syrian and Tunisian music were being offered by all

of them.

In late 1929 the first pinpricks began appearing in the bubble. When Wall Street

crashcd in late October, and panic .subsequently spread throughout the western world,

the effect on the record industry as both immediate and disastrous. By the middle

of 1930 overall sales had dropped dramatically. The answer to this problem, as far

as European companies were concerned, was to close ranks and retrench. In consequence,

the major firms, Columbia, The Gramophone Company, Odeon and their smaller affiliates

amalgamated into the Electrical and Musical Industry Company - EMI for short. While

they were busy tightening belts, technologies that would threaten the dominance of

sound recording were advancing.

By 1931 sound films were the new rage throughout North America and Europe, and

radio, although operative in many parts of the world since the early '20s, now came

of age. The stranglehold that record companies had had on the home entertainment

market was therefore loosened.

Specifically in Arab countries these developments meant that three separate media

now competed for customers' money. The record industry didn't fold, but it did have

to accept that it could only get a slice of pie rather than the whole dish. In 1932

Egypt experienced its first sound film, and, as in India the previous year, the impact

was both immediate and dramatic. In parallel with the Indian experience it also had

the effect of re-focussing both the record companies' goals and of re-shaping the

music itself. Regional styles, while they did not disappear, took second place to

a burgeoning demand for film hits designed to appeal to a wider audience. In effect,

Arab music went 'commercial'. The film hits were popular songs accompanied by orchestras,

many almost western in approach.

Had it not been for the counterbalancing influence of radio, much Arab traditional

music might have withered and fallen from grace during the '30s. However, beginning

in 1934 the I governmentsponsored National Radio actively promoted traditional music

by broadcasting up to eight hours of recordings and live concerts daily. Om Kalsoum,

still the most popular female star, and Mohamed Abd alWahab, her male equivalent,

made a quick and easy transition to this new medium. In fact it promoted Kalsoum

to superstardom. Her monthly radio concerts attracted such huge audiences that virtually

all other activity ceased in Cairo for their duration Om Kalsoum Night became a national

habit .

Radios were cheap, ubiquitous and required no further investment in the way a

gramophone did. Everyone had the opportunity to listen and most did. As a result,

and also partly due to Kalsoum's direct influence, the quality of Egyptian radio

consistently improved throughout the '30s.

Records continued selling throughout all these upheavals, with the giant EMI organisation

still controlling most of the market. Cairo lost some of its pre-eminencc as a recording

centre, partly because the nature of recording itself had changed. With electrical

equipment it was easier to go on location where necessary, but with competition largely

eliminated by the 1931 merger, EMI established single recording centres in key cities

throughout its territories.

Paris became the major centre for the recording of Algerian, Moroccan and Tunisian

musicians. La Voix du Son Maître, EMI's main French label, issued the bulk

of this music on their ‘K’ prefix series and drew often upon musicians resident in

Paris. This fascinating legacy provides us today with an opportunity to listen to

much traditional North African music that might otherwise have gone unrecorded.

[picture of Yususf al-Manyalawi]

The 1939-45 war severely interrupted the Arab music industry. The three major

foreign countries involved in recording all became embroiled in war, and they also

brought their conflict to Arab soil. Despite these events, the hardship they brought

and the consequent shortage of raw materials, the Baidaphon label kept Up a solid

output of new material. Pressing were made for them in neutral Switzerland and throughout

the war Arab communities continued to enjoy both recorded music and radio broadcasts.

After hostilities ended and the companies picked up the pieces, it was more or

less business as usual. From 1946 into the late '50s the industry continued to service

Arab markets, introducing vinyl in from locally owned companies, including Baidaphon

(now renamed Cairophon) and Misriphon challeneged the western conglomerates on home

turf. Throughout the '50s the Northern European recording empire started to fragment

in a variety of complex ways. In Egypt politics and social revolution had something

to do with the waning of influence but technology had a greater impact. Television

was launched in 1960 and, quite naturally, Om Kalsoum made the leap to the new medium

with customary success. TV fascinated the Cairenes as it did almost everyone else

in the world, and the new medium was often used to promote music in the form of concerts

and musical plays. With the advent of tape it was suddenly easier and cheaper to

make records.

With the appearence of cassettes in the early '70s the music fell back into the

hands of small street level entrepreneurs. Music industry protestations that 'home

taping is killing music' had little effect upon either the manufacturer, the retailer

or the customer.

In a 70-year period, a surprisingly large quantity of authentic Arab music has

been preserved for posterity. The roots of current Shaabi and Rai styles speak for

themselves in the old recordings. They are voices worth listening to.

With thanks to Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris; British Library; EMI Archives; Michael

Kinnear; Scott Lund and The National Sound Archive.

Published sources consulted: Popular Musics of the Non Western World (Peter Manual);

Grove Dictionaly of Music & Musicians and notes to CDDA & Ocora CD's.

Recommended Listening: The Frenchbased 'Clube De Disques Arabcs' have reissued

eight volumes of Om Kalsoum covering the period 1926-37 and ten volumes of Mohammed

Abd el-Wahab from 1920 to 1939. They have also compiled a fascinating set by El Hadj

Mrizek, an important Algerian singer from 1930-32 which represents the only currently

available example of early Algerian styles. Yusuf-AI Manyalawi is also represented

by a reissue of some of his best work on this enterprising label. The label is distributed

in England by Sterns; in Paris you can walk into FNAC' and pick them off the shelf.

In London try Virgin; in the U.S., Tower. Or write to them directly at: 125 Bd de

Menilmontant, 75011 Paris. You may see Om Kalsoum's name spelt as Umm Kalthum. It's

the same person. The phonetics are sometimes changed to reflect pronunciation

If you want to dabble first, then Ocora have an excellent CD entitled Archives

de la Musique Arabes 1910-20 which provides important examples of seminal styles

from Egypt and Lebanon in surprisingly high solid quality, and is accompanied by

an excellent and well illustrated booklet in Arabic, English and French. This issue

and all the CDDA's arc also available on cassette Two cassettes of early North African

music exist on the semi-private American Way-hi label. Try your favourite specialist.

There is also vinyl to be had, most of it Egyptian, if you dig deep enough in your

favourite retro storo, junkshop or street market. Good luck

For further reading, the newly published Rough Guide to World Music is the best

place to start, but if you want to get deeper there are several massive tomes that

tell the entire history in depth as well as an annotated glossary of Arabic: musical

terms published by Greenwood Press. Check your library system if you're serious.

This article by Paul Vernon was originally published in the magazine , and I thank

both Paul Vernon and Ian Anderson, the editor of FolkRoots, for their kind permission

to let me include it here.LF-961023

, and I thank

both Paul Vernon and Ian Anderson, the editor of FolkRoots, for their kind permission

to let me include it here.LF-961023

This article was originally published in the magazine FolkROOTS.

Copyright belongs to the author.

Electronic edition by Lars Fredriksson, April 17, 1997